We wish strangers to understand that we did not come here out of choice, but because we were obliged to go somewhere, and this was the best place we could find. It was impossible for any person to live here unless he labored hard and battled and fought against the elements, but it was a first-rate place to raise Latter-day Saints, and we shall be blessed in living here, and shall yet make it like the Garden of Eden; and the Lord Almighty will hedge about his Saints and will defend and preserve them if they will do his will. The only fear I have is that we will not do right; if we do [right] we will be like a city set on a hill, our light will not be hid

Utah is a state of refugees. It was settled by Mormons, fleeing first from Missouri to Nauvoo, Illinois, and then from Nauvoo to Utah. Unlike much of the West, it was not the carrot of economic opportunity that motivated its first colonizers, but the stick of religious persecution. It is quintessentially American in this way––the Mormons as 19th century Pilgrims.

And like the Pilgrims, Mormon colonialism created its own refugees. In the north, Mormon settlers in the Cache Valley pushed the Shoshone off their ancestral land, leaving them to starve. The Shoshone's desperate attacks on the newcomers were retaliated against with the single largest massacre of Native Americans in history.

In the south, non-Mormon settlers were not saved from Mormons' paranoia. In 1857, fearing imminent invasion by the US Army, the Mormon militia massacred over 120 Arkansan emigrants heading for California. They blamed the slaughter on the Paiute, not acknowledging their culpability for another 150 years.

Between these sites, surrounded by the mountains of the Wasatch Range, the Mormons established their enclave in Salt Lake City. On a mountain of violence, both suffered and perpetrated, the Mormons set out to build "God's Kingdom on the earth."

In visiting Utah for a weekend recently, it is perhaps appropriate, then, that I hardly met any actual inhabitants of the state. I was there with my family for two reasons: skiing and the Sundance Film Festival, and each brought its own crowd of contemporary voyagers to the Beehive State.

I arrived on a Thursday in Salt Lake City. The city is laid out on a grid. Mountains enclose the town from all sides, towering above the orderly blocks and wide, straight streets. The streets themselves are remarkably clean. Something about the alpine desert air and white sunlight that purifies everything. This austerity is mirrored in the Utahn Pioneer architecture, descended from the unornamented style of Colonial America. This is combined with the contemporary low-slung, Western style familiar to California and Arizona. Without the geologic activity endemic to these more western states, however, Utahn buildings are often constructed of brick.

The effect is a monotonous, sterile, and sprawling city. The Church of Latter Day Saints considers itself the kingdom of God on Earth. Today, it's mostly metaphorical, but in the past has been taken as a literal exhortation to create Heaven on Earth. Salt Lake City reads as the secularized compromise to this high-minded idealism, a city devoid of the ugliness and chaos that give a place soul, while unable to fully realize the perfect and define splendor of Mormonism's religious architecture.

On Friday, we continued on to Park City and spent the next two days skiing. Park City is home to the largest ski resort in the country, as well as the highest rated, and thousands of wealthy tourists flock there every winter. The crowd is decidedly nouveau riche, mostly millennial, almost entirely white. As I rode up the ski lift on my first day, I sat next to two women, one who was currently living in New York, one who had lived there when she was younger. They discussed how dangerous the city had become, how the younger woman refused to ride the subway after dark now, how expensive everything was and how the rent she paid for a three-bedroom apartment in Manhattan could get her a whole house in the suburbs. Getting off the lift, I skied down past $30-million mansions nestled between runs, past construction sites where more were being built, to the bottom of the mountain that runs directly into the town.

Next to the lift was the steakhouse we would eat at that evening. We sat between two separate groups of men, eight crowded around a circular table, a dozen forced to mold to the L-shaped table in the corner. Judging from their overheard conversations, all the men worked in finance or downstream of it. They wore the usual uniform of Patagonia puffer vests, button ups, and slacks, but with slight evolutions for Trump's return and the death of woke––Pit Vipers, cowboy hats, cowboy boots.

The women, on the other hand, much more ostentatiously celebrated the fall of the liberal elite. Their uniform consisted of fur earmuffs or a wide-brim hat, skinny jeans (2008), Uggs or Moon Boots or cowboy boots, and $50k fur jackets. They stood in groups for hours outside the three clubs the city had to offer, or they sat at bars drinking the state-regulated one-shot drinks doled out through meters on every bottle. Perhaps adopting local mores, the two sexes interacted less than one would expect, and mostly only in preexisting couplings. The environment was distinctly sexless.

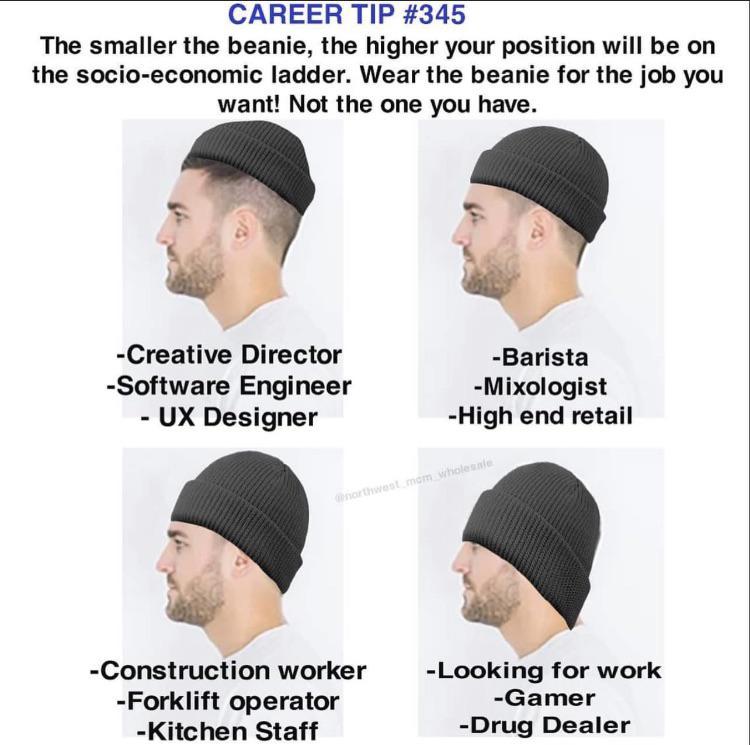

The liberal elite, on the other hand, queued between metal partitions inside plastic tarp tents outside of the public library in anticipation for a coveted Sundance midnight screening. Where the ski crowd overtly flaunted their wealth, this, perhaps richer, crowd showed theirs not in what they wore but in how they wore it. Pristinely distressed Carhartts with New Yorker totes and five o'clock shadow. Blundstones and tiny beanies and Prada purses. Watching football with my dad as a kid, he'd chastise any player who went too far in celebrating a touchdown by saying, "Act like you've been there before!" This is the ethos of quiet luxury, the ethos embodied by the Sundance elite who recently saw their aesthetic go viral in this very town.

The crowd of cinephiles standing outside the theater proved to be even whiter than the skiers. The corporate lawyers and girl bosses, after all, believe in assimilation, and whatever you have to sacrifice, if you can act like them, then they'll invite you on their ski trips. The architects and literati would never want you to sacrifice any part of yourself or your culture, they celebrate difference. So if you want to join them on their vacation, you need to just happen to end up where they're at. And if you don't already share the same interests, references, worldview, and politics, well, hey, that's just the way the cookie crumbles.

We filed into the theater. As the lights dimmed, a land acknowledgement was projected on the screen. "We acknowledge that we are on the ancestral lands of the Ute, Shoshone, Paiute, Diné, and Goshute" over soaring shots of mountains. The history that made these lands only "ancestral" is elided. The mountains soar.

Then, we watched Rabbit Trap, a psychological horror movie about an interracial couple of field recording musicians living in the Welsh countryside who get haunted by a changeling child. Within the film's first five minutes, it becomes obvious that this is all a metaphor for childhood sexual trauma, and by the end, Dev Patel hits the nail squarely on the head when his character says that he tried to forget his father's abuse, but his body wouldn't let him.

The next day, we saw Mary Bronstein's If I Had Legs I'd Kick You, another mental health story, but at least a little more subtle, about a neurotic therapist struggling with her young daughter's eating disorder. Where Rabbit Trap shamelessly regurgitates therapeutic orthodoxy, IIHLIKY asks some more fundamental questions like, "What if some people just aren't fit to be parents?" and, "What if your therapist was a person?" While Rabbit Trap explored ideas that saw their vogue eclipse ten years ago, IIHLIKY will have a slightly longer shelf life, buoyed by a Safdie brother production credit and significant cameos for Conan O'Brien and A$AP Rocky.

The last movie we saw, Hailey Gates' Atropia, was by far the best of the weekend. If Trump is bringing us back to a time before woke, Atropia resuscitates that period's own incoherent morality to fill the void. Set in the US military's Iraq War role-playing facility, Alia Shawkat plays an actor training new recruits by taking on the role of either an Iraqi civilian or terrorist. The fun is in the ambiguity between simulation and reality, between performance and sincerity, between parody and seriousness, between love and lust. No one understands why we're in Iraq, no more now than we did then. This is, of course, an incredibly funny situation. Rabbit Trap is earnest, If I Had Legs I'd Kick You is anxious and pessimistic, and Atropia is silly.

The entire culture war is silly. All the VC bros who now feel emboldened to say "retard" with their friends on their ski trips and all the coastal nepo babies who now re-post ICE infographics (and also feel like they can say "retard" with their friends, but not in public)——both groups have more in common than they'd care to admit. But they're mutually unintelligible, they can't see past the narratives that are ready-made for them to care about. There'll be another Iraq War one of these days and neither group will care enough to figure out why the hell we're fighting because neither side will be doing any of the actual fighting.

We're at a global societal local minimum. Like an alpine valley, like Salt Lake City or Park City. The past two hundred years have brought us higher than we've ever been, higher than the plains of Missouri or Illinois, and we're surrounded by mountains now, their peaks soaring around us. But we can't reach them and, in fact, their proximity only causes us more yearning and pain than their distant sight from lower ground, where they were mere abstractions. Our attempts to summit the mountains around us, to achieve Heaven on Earth, have only hurt us in the past, and so we have mostly given up trying. We occupy ourselves instead by building anthills and knocking them over.

But now, our valley is on fire, and we will soon have no choice but to set out to climb these mountains again. Who's to say whether we'll find our footing at the top, or come crashing back down to the bottom!